Barriers Families Face When Helping Their Mentally Ill Family Member

Abstract

A minority of children and adolescents with mental health problems access handling. The reasons for poor rates of treatment access are not well understood. As parents are a key gatekeeper to handling access, it is important to establish parents' views of barriers/facilitators to accessing treatment. The aims of this study are to synthesise findings from qualitative and quantitative studies that study parents' perceptions of barriers/facilitators to accessing treatment for mental wellness issues in children/adolescents. A systematic review and narrative synthesis were conducted. Forty-iv studies were included in the review and were assessed in item. Parental perceived barriers/facilitators relating to (1) systemic/structural problems; (2) views and attitudes towards services and treatment; (3) noesis and understanding of mental health problems and the help-seeking process; and (4) family circumstances were identified. Findings highlight avenues for improving admission to child mental wellness services, including increased provision that is free to service users and flexible to their needs, with opportunities to develop trusting, supportive relationships with professionals. Furthermore, interventions are required to improve parents' identification of mental health issues, reduce stigma for parents, and increment awareness of how to access services.

Introduction

Mental health disorders are common amongst children and adolescents, with an estimated prevalence rate of 13.4% [1]. Youth is a time of heightened risk for mental health disorders, with one-half of all lifetime mental health disorders emerging before the age of 14 years [2]. Moreover, the negative affect of poor mental health early on in life extends into machismo, predicting poor academic outcomes [three], increasing the risk of subsequent mental wellness problems [4] and high rates of mental health service use [5], reducing life satisfaction [half-dozen], and creating a heavy economic brunt for order [7].

In recent decades, there has been a rapid growth in the evolution of prove-based treatments for mental health disorders in childhood and adolescence; and the lasting benefits of intervening early on are well established [8, 9]. Nonetheless, poor rates of treatment access take been repeatedly reported, and national surveys in the UK, Commonwealth of australia, and U.s. take estimated that only 25–56% of children and adolescents with mental health disorders access specialist mental health services [10–12], with especially low rates of access for internalising compared with externalising problems [ten, 12].

In an effort to explain the unmet need in relation to childhood mental health disorders, studies take oftentimes focused on identifying predictors of service use. Family and child characteristics, including ethnicity, family unit socioeconomic, and insurance status, living in an urban or rural area, and severity of the child's problems have all been implicated in determining the likelihood of service utilization. Overall studies propose that being Caucasian [13, 14], having insurance coverage (in the USA) [xv, 16], living in an urban area [17], and having a kid with more severe mental health bug [12] increases the likelihood of a family accessing treatment. While these studies shed some light on who accesses treatment, they tell us little nigh the reasons for discrepancies in service employ or the processes underlying accessing treatment.

An alternative arroyo draws on models of assist-seeking behaviour to conceptualise different stages and processes involved in accessing treatment for mental health issues in children and adolescents [16, 18, 19]. Specifically, factors have been explored that underlie the distinct stages of (ane) parental recognition of difficulties, (ii) the decision or intention to seek help, and (three) contact with services. Studies of parental recognition suggest that parents who perceive that a trouble exists and remember that the problem has a negative impact on family life are more likely to seek help and access mental wellness services for their children than those who do not recognise a trouble or its negative affect [20, 21]. Parental attitudes surrounding mental wellness and mental wellness services take been shown to influence help-seeking decisions—in detail, behavior that mental health problems are caused by kid'due south personality or relational issues [22], negative perceptions of mental health services [18], and perceived stigma associated with mental health problems [23, 24] have all been associated with reduced aid-seeking behaviour. Similarly, 'logistical' factors (such as transport access and flexibility of appointment system) have been shown to influence the likelihood of a family unit having contact with services [25, 26]; and a parent sharing concerns nigh a child'due south mental health with a primary care practitioner has likewise been shown to improve access to mental health services [27, 28].

Together these studies highlight the cardinal 'gatekeeper' or 'gateway provider' [29], office parents tin can play in treatment access for mental wellness issues for children and adolescents, and signal towards numerous potential barriers parents may face in the process of seeking and obtaining help. However, to improve access to handling, it is important to establish parents' own views on the factors that may help and hinder admission. Indeed, studies focusing on ongoing treatment appointment (i.e., standing treatment after initial admission) have identified fundamental factors that parents perceive to be barriers to treatment attendance [thirty, 31], and thereby highlight areas to target to better treatment retentiveness. Therefore, similarly, identifying what parents perceive to exist the barriers and facilitators to the initial access to treatment would highlight areas to target to improve rates of admission.

A recent systematic review synthesised findings across studies that reported young people's perceptions of barriers and facilitators to accessing mental wellness treatment [32]. However, given that children and adolescents are rarely able to seek and access help alone, information technology is every bit of import to establish parents' corresponding views; a review of parents' perceptions of barriers and facilitators to handling access has not been conducted to date. The purpose of this study is to systematically review studies that report parents' perceptions of barriers and/or facilitators to accessing treatment for mental wellness problems in children and adolescents. The review synthesises findings across both quantitative and qualitative studies, incorporating studies that focus on specific mental health disorders, as well as those considering emotional and/or behavioural problems more broadly. The review focuses on access to psychological treatments (rather than medication), and is concerned with the processes of both seeking and obtaining help through specialist mental wellness services, besides as primary care and school settings.

Method

A systematic literature review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines [33].

Literature search

Iv electronic databases were searched in October 2014. The NHS Evidence Healthcare Database was used to run a combined search of Medline, PsychInfo, and Embase; and the Web of Science Cadre Collection was searched separately. With reference to relevant literature and previous reviews, search terms to reflect the following iv key concepts were generated: barriers/facilitators; help-seeking; mental health; and parents/children/adolescents. Search terms inside each of these four categories were combined using 'AND' to search titles/abstracts. Searches were limited to articles published in English language (see Electronic supplementary material i for details of search strategy).

Additional hand searching methods were also employed. The reference lists of relevant articles in the field identified through the database search were scanned for boosted studies. Citations of relevant articles were so searched to help identify more contempo studies non yet included in the electronic databases.

Report eligibility

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were drafted and then refined after piloting using a pocket-sized sample of papers (see Electronic supplementary material 2 for details of total criteria). A study was selected for inclusion if:

- ane.

parents/caregivers of children/adolescents were participants. Studies were excluded if the hateful age of the children/adolescents was over 18 years or the sample included adults over 21 years;

- ii.

parents'/caregivers' perceived barriers/facilitators to accessing treatment for mental wellness problems in children or adolescents were reported. Studies that only reported barriers/facilitators perceived past children/adolescents were not included;

- three.

the study was published in English in a peer-reviewed journal. Reviews were excluded.

Studies reporting quantitative or qualitative data (or both) were included. There was no requirement relating to the nature of the mental health problem; studies focusing on either a specific mental health disorder (e.grand., depression, ADHD) or behaviour and/or emotional problems more than generally were included. However, studies that merely reported factors associated with or predictors of assistance-seeking or service use were not included. Similarly, studies reporting outcomes of an intervention targeted at overcoming one or more than barriers to help-seeking were not included. As the focus of the review was barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatments inside the general population, studies focusing on access within a special population (east.yard., children/adolescents with intellectual disability and children/adolescents with mental health issues in the context of a specific concrete wellness condition); and studies specifically addressing access to medication or inpatient psychiatric care (as these would rarely be the first-line treatments), or parenting programmes not specifically targeting mental health bug in children/adolescents were not included.

Study option

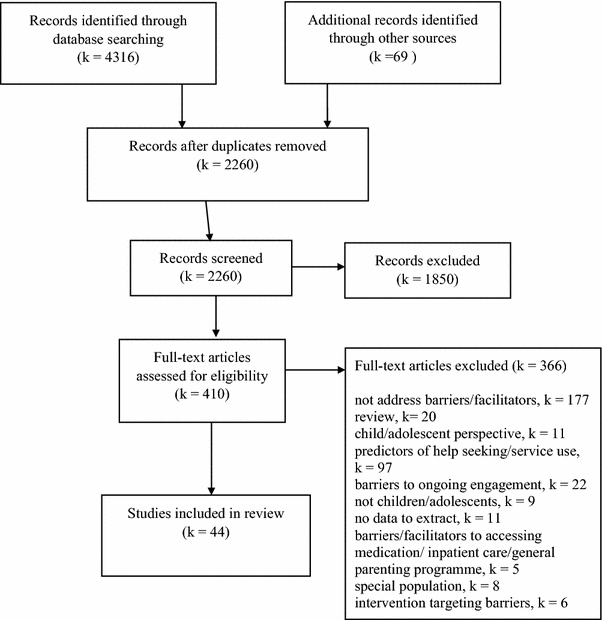

Details of the study option procedure are provided in the flowchart in Fig. ane. The combined electronic database search retrieved 4316 records, leaving 2191 records after duplicates were removed. Hand searching identified additional 69 potentially eligible papers. Ii independent reviewers (TR and MB/LS) then screened the 2260 titles and abstracts and excluded studies using the criteria detailed to a higher place. Understanding between reviewers was good (85% understanding). If either reviewer selected the study for potential inclusion, the full paper was sourced. Ii reviewers (TR and MB/LS) then independently assessed the 410 full papers for inclusion, and if the study failed to see inclusion criteria, the master reason for exclusion was recorded. In cases of disagreement in inclusion/exclusion sentence, the paper was passed to a third contained reviewer (CC) and a final decision was agreed. In total, 44 studies met criteria for inclusion in the review.

PRISMA flowchart

Data extraction

Two standard data extraction forms were adult: one for studies reporting quantitative information and a 2nd for studies reporting qualitative information. The extraction forms were drafted and then refined after the initial piloting past reviewers. Two reviewers (TR and MB or LS) and then independently extracted data for each included written report, using the respective extraction form (or in the case of mixed method studies, using both forms). Whatsoever discrepancies in extraction were discussed between the 2 reviewers, and if there were differences in interpretation, a third reviewer (CC) was consulted and a consensus agreed.

The following data was extracted for each included study: (1) methodology used (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods); (2) country of written report; (iii) report setting (e.one thousand., mental health clinic, school); (four) parent/caregiver characteristics (number and percentage of mothers); (5) kid/boyish characteristics (age range, mental health status, mental health service use, blazon of mental health problem, or disorder); and (6) whether the written report targeted a item indigenous grouping or urban/rural population. For studies that nerveless and analysed quantitative information, details relating to the measure of barriers/facilitators were besides extracted (e.g., name of measure, number and format of items, content of items [e.one thousand., subscales, broad areas covered], whether it is a published measure or developed for the written report). Where studies reported qualitative data, the method used to collect data (e.g., focus groups, interviews) and areas of relevant questioning were recorded. Finally, data relating to parental perceived barriers/facilitators was extracted from the results department, including the proper name of each reported barrier and facilitator and associated show (e.1000., number of participants who endorsed the barrier/facilitator, participant quotes).

Quality rating

The quality of included studies was assessed using modified versions of the two checklists developed by Kmet and colleagues [34]. Ane checklist was specifically designed for apply with quantitative studies and the other for use with qualitative studies, thus allowing respective evaluations of unlike report designs; and studies that used mixed methods were assessed using both checklists. Items on the checklist for assessing the quality of quantitative studies that were not relevant to studies included in this review were removed (due east.grand., 'If interventional and random resource allotment was possible, was it described?'); and the wording of other items was tailored for the purpose of this review (eastward.g., 'Measure of barriers/facilitators well defined'). Items on the checklist for assessing the quality of qualitative studies were slightly modified to incorporate Dixon-Woods' [35] prompts for appraising qualitative research (east.g., 'Are the inquiry questions suited to qualitative inquiry?'). Items on both checklists are rated on a three-bespeak calibration (yes = 2, partial = ane, and no = 0), with a maximum score of twenty on the quantitative checklist and xviii on the qualitative checklist. Items on each checklist that related to methods of data collection, information analyses, and conclusions drawn were judged specifically in relation to the part of the study that focused on parental perceived barriers/facilitators (run across Electronic supplementary material 3 for modified versions of checklists). Based on the final score, studies were classified into three groups to reflect the overall spread of quality ratings across studies, including: low (quantitative: 0–12; qualitative: 0–11), medium (quantitative: 13–16; qualitative: 12–15), and high (quantitative: 17–twenty; qualitative: 16–18) quality.

Two reviewers (TR and MB/LS/KH) independently assessed the quality of each included study. Twenty studies were rated using the checklist for quantitative studies, twenty-ii studies were assessed using the checklists for qualitative studies, and two studies that used both qualitative and quantitative methods were assessed using both checklists. The 2 reviewers discussed whatsoever discrepancies in ratings, and, if necessary, consulted a 3rd reviewer (KH or CC) to achieve a terminal decision.

Data synthesis

A narrative synthesis was conducted, drawing on the framework and techniques described in 'ERSC Guidance on Conducting Narrative Synthesis' [36]. Initially, preliminary syntheses of the quantitative data and the qualitative data were each conducted separately. Tabulated quantitative data were reorganised to group findings according to reported perceived barriers/facilitators, and and then, a code was attached to each individual reported bulwark/facilitator. Data were reorganised according to the initial codes, and then, an iterative process was adopted in which codes were refined, and grouped into overarching emerging barrier/facilitator themes. Tabulated qualitative data were then coded and organised into barrier/facilitator themes, following the same iterative process. The next step was to develop a 'common rubric' [36] to anneal quantitative and qualitative findings. This involved refining quantitative and qualitative codes, to develop a single-coding framework, that described and organised the barriers/facilitators identified beyond all studies.

To facilitate the procedure of comparing and contrasting findings beyond studies, and in item to examine variation in the number of participants who endorsed particular barriers/facilitators, further 'transformation' [36] of quantitative data was performed. Get-go, where applicative, responses on Likert response scales were converted into 'per centum endorsed' by summing positive responses (e.1000., summing number of 'concord' and 'strongly agree' responses). Side by side, the 'pct endorsed' for each barrier/facilitator was examined and categorised into three groups according to the relative overall spread of endorsement rates beyond studies ['small-scale' (0–10%), 'medium' (10–30%), and 'large' (more than 30%)]. Graphical representations were then used to display the percentage of studies that reported individual barriers and facilitators, illustrating the percentage of quantitative studies in which the barrier/facilitator was reported by at least a 'medium' percentage of participants, as well as the percentage of qualitative studies that reported corresponding barriers/facilitators. Similarities and differences in written report findings, and the relationship between individual barriers/facilitators, and bulwark/facilitator themes, were further explored using data extracted in relation to study characteristics (eastward.chiliad., written report setting, sample characteristics, and mental health service use).

Finally, to assess the robustness of the data synthesis, a sensitivity analysis was performed in which findings from studies assessed to exist of 'low' quality were removed, and the remaining data were re-examined to decide if the codes, fundamental themes, and conclusions remained unchanged.

I reviewer (TR) conducted the data synthesis, with regular discussion with squad members (CC, KH, and DO'B) to hold interpretation of data and formulation of codes and themes.

Results

Clarification of included studies

In full, 44 studies were included in the review, with 20 studies providing quantitative data, 22 providing qualitative information, and 2 providing both quantitative and qualitative information. Details related to the study characteristics are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

The studies varied widely on a number of characteristics, including state (with the largest number from the Us); age range (with variable age range, and some focusing on younger/older age groups); demographic profile (with some urban or rural populations, and some studies of immigrant groups or particular ethnic/racial groups); method of recruitment and report settings (with samples recruited through various customs settings or through mental wellness service providers); mental health status of participants (with samples of parents of children with mental health bug/diagnosis or without mental health bug); nature of mental health trouble (with some studies focused on mental health issues, in general, and others focused on specific mental health problems); and extent of mental wellness service use (with samples of current/previous service users or referrals, those with a history of help-seeking/prior receipt of a mental health diagnosis, non-service users, a minority of service users/varying levels of service apply, or service utilize was not reported).

Studies providing quantitative data tended to measure parental perceived barriers using a questionnaire that asked participants to either endorse the presence or absence of barriers from a list or rate barriers on a 3–5 point Likert response scale. Some quantitative studies, however, asked more open questions well-nigh the reasons for not seeking help or difficulties associated with seeking assist/attending services/accessing services. Just two quantitative studies provided data relating to perceived facilitators of accessing mental health services [37, 38]. The amount of relevant quantitative information reported beyond studies ranged from data relating to responses to a single question [39, 40] or particular questionnaire subscales [23], through studies reporting a breakdown of responses to a large number of questionnaire items [26, 38, 41].

Qualitative information relating to perceived barriers and facilitators tended to be collected using interviews and/or focus groups, with a minority using written questionnaires. All qualitative studies provided information relating to perceived barriers, and thirteen provided data relating to perceived facilitators. Similar quantitative studies, the amount of relevant data provided by qualitative studies varied considerably, with perceived barriers/facilitators to treatment admission only forming a very small part of some studies [42, 43], and the primary focus of others [44, 45].

Quality ratings

Every bit shown in Tables 1 and two, quality ratings of quantitative studies ranged widely from eight to 19 (out of a possible 20); and corresponding ratings of qualitative studies similarly ranged from seven to eighteen (out of a possible 18). Research questions, written report design, participant selection, and sample size were mostly assessed positively for quantitative studies; whereas methods of data collection, analyses, and reporting of findings specifically in relation to perceived barriers/facilitators were areas of weakness beyond lower quality studies. Evidence of robust evolution and evaluation of the measure of barriers/facilitators amidst the target population was lacking across all quantitative studies.

Similarly, research questions, report context, and overall report blueprint were generally well described and advisable across qualitative studies, only the barrier/facilitator data collection methods and data analysis were often not conspicuously described among lower quality studies, and the credibility of the findings amid these studies was oft limited.

Quantitative and qualitative data synthesis

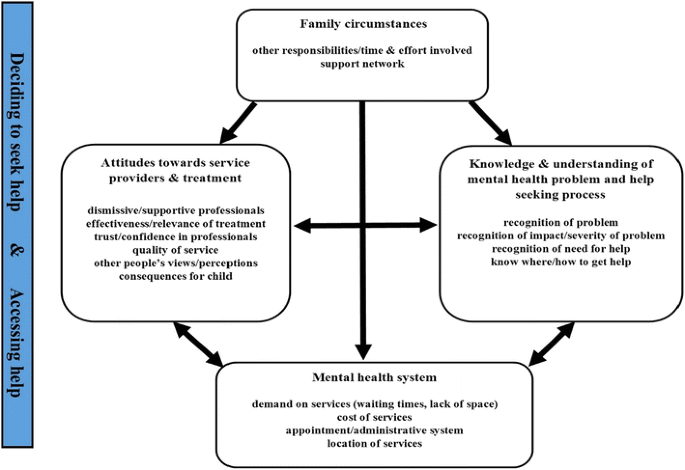

As illustrated in Fig. 2, perceived barriers and facilitators relating to four inter-related themes emerged: (i) systemic and structural issues associated with the mental health system; (two) views and attitudes towards services and treatment; (3) knowledge and understanding of mental health problems and the aid-seeking process; and (iv) family circumstances. Perceived barriers/facilitators inside each theme are summarised below Footnote 1 and outlined in detail in Electronic supplementary material iv.

Perceived barrier/facilitator themes

Systemic-structural barriers and facilitators

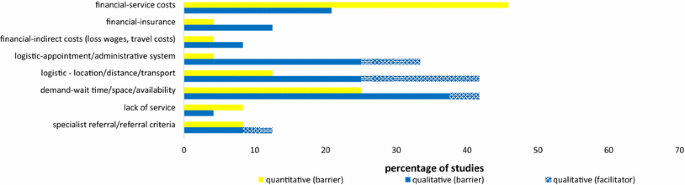

Effigy 3 illustrates the range of barriers and facilitators relating to systemic-structural aspects of mental wellness services that were reported across quantitative and qualitative studies.

Perceived systemic-structural barriers and facilitators: Percentage of quantitative* and qualitative** studies to study each barrier/facilitator. *Pct of quantitative studies = Percentage of 24 included samples where a 'medium' (10-xxx) or 'big' (>30) percentage of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator. **Percent of qualitative studies = Per centum of 24 included studies that reported the bulwark/facilitator

The cost of mental health services was reported to be a barrier by more than than 10% of participants across virtually half of quantitative studies [26, 37, 46–53]; and amidst a smaller number of qualitative studies [54–58]. With a few exceptions, these studies were all conducted in USA and participants were typically not mental health service users. Other financial barriers identified in fewer quantitative and qualitative studies included a lack of insurance coverage (in USA studies) and indirect costs (eastward.one thousand., loss of wages and travel costs).

Various logistical-type barriers and facilitators were identified. Quantitative studies often asked participants to rate 'inconvenient (date) times' as a possible barrier, although typically, only a minor minority of participants rated this every bit a bulwark [38, 41, 53, 59]. Qualitative studies also identified the cumbersome administrative system [56] and various aspects of the date system [44, 45, 57, 61] as perceived barriers/facilitators. Both quantitative and qualitative studies highlighted the location of service providers and the availability of transport every bit logistical barriers for some families; and the potential benefit of providing logistical back up for families was besides noted in qualitative studies.

The demands on services, and in particular, the wait to access services were a recurring systemic-structural barrier reported across quantitative [41, 49, 51, 52, 64] and qualitative [44, 55, lx, 61, 65–69] studies from unlike countries, particularly among samples of service users. Studies too identified a consummate lack of specialist services and referral criteria as perceived barriers/facilitators.

Attitudes towards service providers and psychological treatment

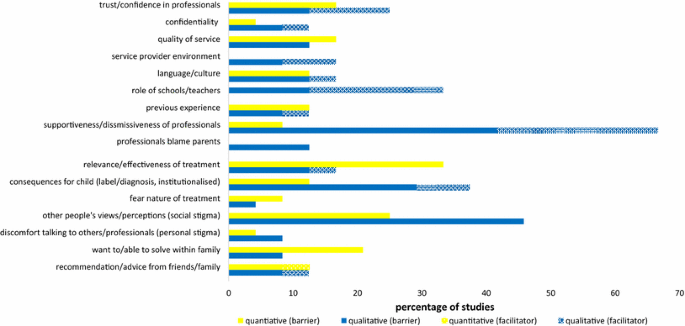

Effigy 4 illustrates the broad range of views and attitudes relating to professionals, unlike elements of service providers, and the consequences of seeking and receiving psychological treatment that were identified equally barriers/facilitators beyond studies.

Perceived barriers and facilitators related to attitudes towards service providers and psychological handling: Percentage of quantitative* and qualitative** studies to written report each barrier/facilitator. *Percentage of quantitative studies = Percentage of 24 included samples where a 'medium' (10-30) or 'large' (>30) percent of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator. **Per centum of qualitative studies = Percent of 24 included studies that reported the barrier/facilitator

Trust and confidence in professionals and the being/absence of a trusting relationship with professionals were reported as a bulwark/facilitator in both quantitative [26, 38, 46, 70] and qualitative studies [45, 55, lx, 63, 66, 71]. Concerns surrounding confidentiality of discussions with professionals, broader perceptions of the nature, and quality of services, and the previous feel with services were also identified every bit perceived barriers/facilitators among quantitative and qualitative studies. A perceived language or cultural bulwark/facilitator was specifically reported among samples of minority populations; and the service provider environs and specific views towards teachers/schools emerged as potential barriers/facilitators in qualitative studies.

The attitudinal barrier reported past parents in the largest number of (predominantly qualitative) studies was the feeling of not beingness listened to or dismissed by professionals. A sense of parents feeling dismissed emerged among 10 (42%) qualitative studies [42, 45, 46, 60, 61, 66, 67, 69, 73, 75]; and several qualitative studies [45, 61, 66] too reported that parents felt 'blamed' by professionals. On the other mitt, a quarter of qualitative studies [45, 46, 55, 58, 61, 75] reported that perceiving that wellness professionals heed to voiced concerns encouraged parental help-seeking.

Diverse beliefs surrounding the consequences of assist-seeking, for example, the relevance/effectiveness of treatment, the potential consequences for the child, and fears associated with the handling itself were all identified among some studies as posing barriers/facilitators to help seeking. The about commonly reported bulwark related to concerns surrounding the consequences of help seeking, however, was the barrier posed by the perceived negative attitudes among other people. The 'stigma' associated with mental health bug or attention mental wellness services was reported as a barrier in studies from different countries and cultures, including 11 (46%) qualitative studies [45, 54, 55, 57, 58, threescore, 61, 63, 69, 71, 75], and among at least 10% of participants in six (25%) quantitative studies [twoscore, 41, 46, 47, 49]. More than 'personal stigma' or negative cocky-evaluation amidst parents, and discomfort talking most a child'due south difficulties; a desire to solve problems within the family; and the office of advice from family/friends, were also all highlighted as deterring or encouraging aid seeking in several quantitative and qualitative studies.

Knowledge and agreement of mental health problems and the help-seeking procedure

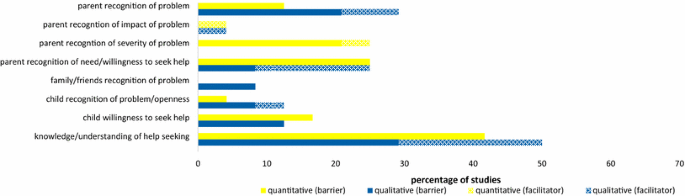

Figure 5 illustrates that the barriers and facilitators reported across studies relating to awareness and understanding of both child mental health problems and the process of seeking professional person help for these problems.

Perceived barriers and facilitators related to knowledge and understanding of a child'south mental health problem and the help-seeking process: Per centum of quantitative* and qualitative** studies to report each barrier/facilitator. *Percentage of quantitative studies = Per centum of 24 included samples where a 'medium' (10–30) or 'big' (>thirty) percent of participants endorsed the bulwark/facilitator. **Percentage of qualitative studies = Percentage of 24 included studies that reported the barrier/facilitator

Parental recognition of (1) the being of a child'south mental health problem, (2) the severity of the problem, and (3) the associated impact was each reported every bit perceived barriers/facilitators to help seeking among a number of studies. Similarly, between 12 and 26% of parents reported not wanting/not needing help across a quarter of quantitative samples [38, 49, 50, 70, 76], and recognition of the need for help or parental willingness to seek aid was similarly cited as barriers/facilitators to aid seeking in a number of qualitative studies [44, 58, 74, 75, 78]. A lack of family recognition, the presence/absence of recognition by the child themselves, and a child's ain reluctance to seek help were besides reported every bit helping/hindering aid seeking in some studies.

Among 10 (42%) quantitative samples [26, 41, 47, 51–53, 59, 70, 77], at to the lowest degree 14% (and upwards to 75%) of participants reported a lack of noesis almost where or how to get help equally a barrier. This lack of noesis most where to become to ask for help and how to go nearly getting help was corroborated in a number of qualitative studies [45, 56, sixty, 78]. Qualitative studies [45, 46, 55, 58, 61, 63, 69, 71, 73] also highlighted that wider parental agreement of the mental health arrangement as well acted as a barrier/facilitator to help seeking.

Family circumstances

Equally displayed in Fig. 6, other barriers/facilitators reported in studies related to additional specific aspects of family circumstances, including other responsibilities and commitments, and the time commitment involved in aid seeking; and the family unit's support network.

Perceived barriers and facilitators related to a family's circumstances: Percentage of quantitative* and qualitative** studies to report each barrier/facilitator. *Pct of quantitative studies = Percentage of 24 included samples where a 'medium' (10–xxx) or 'big' (>thirty) percentage of participants endorsed the barrier/facilitator. **Percentage of qualitative studies = Percentage of 24 included studies that reported the barrier/facilitator

Robustness of data synthesis

Studies assessed to be of low quality (half dozen quantitative studies and 5 qualitative studies) were removed, and bulwark/facilitator codes and themes were re-examined. This sensitivity analysis showed that the overall synthesis remained unchanged when limited to higher quality studies simply.

Discussion

This review synthesised findings from 44 studies addressing parental perceptions of barriers/facilitators to seeking and accessing help for mental health issues in children and adolescents. Perceived barriers/facilitators related to four key themes emerged across studies (displayed in Fig. ii).

In relation to systemic-structural issues surrounding the mental health organisation, the demand on services emerged as a perceived barrier internationally, reported in studies conducted in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland, United states, Australia, and Canada. Importantly, waiting times and difficulty getting a referral were most commonly reported as barriers amid samples of service users, suggesting that it is later on some experience of waiting to access services (or experiencing difficulty accessing services) that these issues ofttimes get most pertinent to families. In contrast, the barrier posed by the cost of services (or associated insurance issues) was most often reported among community samples in USA, suggesting the 'threat' of paying fees to access services can really deter families from attempting to seek help at all. Other indirect costs associated with service use, such as loss of wages and travel costs, were less commonly reported equally barriers inside and beyond studies, just, nevertheless, highlight how certain family circumstances (e.m., living in a rural expanse) may increment the likelihood that aspects of the mental health organization nowadays a barrier to access. Equally, findings indicated that some parents perceive logistical aspects of mental wellness systems (such equally the appointment/administrative system and the location of services) every bit both barriers and facilitators to seeking and accessing help—just the wide variation in the frequency with which these issues were reported across studies highlights how both variations in mental wellness systems (e.g., presence/absenteeism of flexible appointment systems/user-friendly services) and variation in family unit circumstances (e.g., admission to transport and fourth dimension bachelor to attend appointments) may influence the likelihood that parents perceive such problems as barriers.

A range of views and attitudes towards services and handling emerged as perceived barriers/facilitators, and notably, these views and attitudes often appeared to be shaped by the previous feel with the mental health system (or contact with services/professionals more than generally). In particular, feeling not listened to or dismissed/blamed by professionals was frequently reported as a bulwark to seeking and accessing help across qualitative studies; and equally, the perceived benefit of 'supportive' professionals was likewise evident. Similarly, trust and conviction in professionals, views surrounding the quality of services, and views relating to specific professionals (e.m., teachers, GPs) were all identified equally presenting barriers/facilitators to both seeking and accessing help across various samples. Other attitudinal barriers/facilitators related to the consequences of treatment also emerged, including beliefs surrounding the effectiveness or relevance of treatment, fears surrounding the negative consequences of treatment, and fears associated with treatment itself. Still, more notable was the frequency with which parents across studies reported the detrimental impact of perceived negative attitudes of others (as well as personal discomfort surrounding mental health) on help seeking.

Knowledge surrounding both mental health problems and the help seeking process emerged as perceived barriers and facilitators across a wide range studies. The large number of studies—and the large number of participants within some studies—that reported barriers related to not knowing where or how to seek help was especially salient. Interestingly, among studies that addressed recognition of a child's mental wellness problem, relatively big numbers of parents reported perceived difficulties identifying a problem (or a child's lack of recognition) as a barrier to seeking assist, and similarly, parents' perception of the importance of recognition of the severity and impact of a problem was besides clear in some studies.

Perceived barriers/facilitators relating specifically to family circumstances, such every bit other commitments or responsibilities and a family's back up network, were less commonly directly addressed in studies than other types of barriers/facilitators. Nevertheless, these issues were raised in qualitative studies, and reported by a sizeable minority of participants in several quantitative studies, thus highlighting the role family unit circumstances tin can play. Moreover, the potential impact of other aspects of a family'south circumstances (east.g., prior contact with mental wellness services, living in a rural surface area, access to transport, linguistic communication spoken) on the experience of other types of barriers was also clearly illustrated.

Implications

This review highlights several primal areas of potential intervention to minimise barriers to assistance seeking to improve rates of handling access for mental health issues in children. In relation to mental wellness systems, information technology is evident that ensuring service provision is sufficient, and available costless of charge would remove cardinal barriers to seeking and accessing professional help. Minimising the 'cumbersome' nature of mental health systems and offering flexible services would also make seeking assistance easier for many families (e.g., providing driblet-in services in local community settings, such equally schools and primary care facilities). Moreover, the potential benefit of ensuring professionals working inside the mental health system (primary care, schools and specialist services) accept the opportunity and skills to develop trusting relationships with families, adopt a supportive approach, and communicate well with other professionals was equally axiomatic.

In add-on to improvements to mental health systems, the potential benefit of targeted approaches to improving public knowledge and agreement of childhood mental health difficulties and the help-seeking procedure was also illustrated. Equipping parents with knowledge and tools to help them identify mental health bug in children, as well as specifically targeting stigmatising attitudes towards parents and the civilisation of parental 'arraign' would help to overcome key barriers to help seeking. Moreover, raising awareness and understanding of the professional assist that is available and the process involved in seeking assist for childhood mental health problems could help provide families with the necessary knowledge about where and how to seek help, as well as foster positive attitudes towards the potential benefits of psychological handling.

Strengths and limitations

By focusing on parents' own perspective surrounding the help-seeking process, this review importantly extends what is known from enquiry specifically addressing the predictors of service use. Notably, the wide range of perceived barriers/facilitators identified here illustrates the plethora of factors at play in determining the likelihood that a family will access services. Findings from quantitative studies shed light on the number of parents who perceive particular barriers at unlike stages of the assistance–seeking procedure; and qualitative studies provided further detail on the specific nature of barriers and corresponding facilitators, as well equally identifying additional issues that were not addressed in questionnaire studies. Variation in findings across studies helped illustrate who may and may not experience item barriers/facilitators and the relationship between barriers/facilitators across the key themes.

Studies included in the review varied widely in terms of blueprint and primary purpose, the corporeality of data relevant to the review, participant populations, and measures of barriers/facilitators. While similarities and differences across study characteristics were explored, due to the broad variability in sample characteristics, it was not possible to behave out more detailed sub-group analyses examining factors associated with perceived barriers/facilitators, e.k., the age of the child/boyish, study setting, child/adolescent mental health status, or the blazon of mental wellness problem. Although removing the poorest quality studies from the analysis did not bear on on the overall findings, it is likewise important to acknowledge the wide variation in quality of studies included in the synthesis. The lack of well-evaluated measures of perceived parental barriers/facilitators specifically in relation to help seeking for childhood mental health bug presented a limitation beyond quantitative studies. Indeed, the fact that barriers/facilitators were reported in qualitative studies that were not addressed in the questionnaires illustrates limitations with existing questionnaire measures. Moreover, a big number of both qualitative and quantitative studies focused on parents of children who had accessed services, and therefore, the review was limited in the extent that it was able to address barriers among families who take not reached services. Information technology is likewise important to annotation that the systematic search used to identify studies for inclusion in this review was conducted in October 2014, and therefore, any relevant studies published since this data were not included in the review.

The available literature highlights the need for improvements to child mental wellness services and interventions to raise public awareness and understanding of childhood mental health difficulties and how to access bachelor services. However, further investigation into parents' perceptions of barriers and facilitators to seeking and accessing handling for mental health issues in children and adolescents is needed. Specifically, findings from qualitative studies should inform the development of questionnaire measures to ensure all relevant barriers/facilitators which are captured and can be quantified. For example, qualitative studies have highlighted the need to address parents' perceptions of the dismissiveness/supportiveness of professionals in barrier/facilitator measures—an area frequently neglected in quantitative studies to engagement. Studies also need to focus on community populations to develop a fuller understanding of varying factors that help and hinder parents at all stages of the help-seeking process. Closer examination of variation in the perceived barriers/facilitators among parents of children of different ages and across dissimilar mental wellness disorders is as well necessary to inform more tailored approaches to better access to treatment.

Notes

-

Ii quantitative studies reported data relating to perceived barriers/facilitators for 2 sub-samples (a sample of service users and non-service users [41]; and a sample with depression and without depression [49])—and these sub-samples were treated separately in the post-obit analyses

References

-

Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA (2015) Almanac inquiry review: a meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56:345–365

-

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-Four disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62:593–602

-

Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM (2001) Life course outcomes of young people with feet disorders in boyhood. J Am Acad Kid Adolesc Psychiatry xl:1086–1093

-

Pino DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Beck J, Ma Y (1998) The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with feet and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 55:56–64

-

Knapp M, McCrone P, Fombonne E, Beecham J, Wostear K (2002) The Maudsley long-term follow-upward of child and adolescent depression. Br J Psychiatry 180:19–23

-

Layard R, Clark A, Cornaglia F, Powdthavee Due north, Vernoit J (2014) What predicts a successful life? A lifecourse model of wellbeing. Econ J 124:F720–F738

-

Fineberg NA, Haddad PM, Carpenter L, Gannon B, Sharpe R, Young AH et al (2013) The size, burden and cost of disorders of the encephalon in the UK. J Psychopharmacol 27:761–770

-

Wolk CB, Kendall PC, Beidas RS (2015) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for child anxiety confers long-term protection from suicidality. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54:175–179

-

Ginsburg GS, Becker EM, Keeton CP, Sakolsky D, Piacentini J, Albano AM et al (2014) Naturalistic follow-up of youths treated for pediatric anxiety disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71:310–318

-

Green H McGinnity Á, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R (2005). Mental health of children and young people in U.k., 2004. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

-

Lawrence D, Johnson Southward, Hafekost J, de Haan KB, Sawyer M, Ainley J et al (2015) The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents: Study on the Second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing

-

Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein G, Swendsen J, Avenevoli S, Case B et al (2011) Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.Due south. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 50:32–45

-

Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB (2002) Unmet need for mental wellness care among U.South. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry 159:1548–1555

-

Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey Grand, Stein MT (2004) Kid anxiety in primary intendance: prevalent but untreated. Depress Anxiety 20:155–164

-

Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer EM, Fairbank JA, Burns BJ, Keeler K et al (2002) Psychiatric disorder, harm, and service utilise in rural African American and white youth. Arch Gen Psychiatry 59:893–901

-

Zwaanswijk K, Verhaak PF, Bensing JM, Van der Ende J, Verhulst FC (2003) Help seeking for emotional and behavioural problems in children and adolescents: a review of contempo literature. Eur Kid Adolesc Psychiatry 12:153–161

-

Cohen P, Hesselbart CS (1993) Demographic factors in the use of children'due south mental health services. Am J Public Wellness 83:49–52

-

Logan D, King C (2001) Parental facilitation of adolescent mental wellness service utilisation: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 8:319–333

-

Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez Thousand, Paradise G, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D et al (2002) Cultural and contextual influences in mental health aid seeking: a focus on ethnic minority youth. J Consult Clin Psychol lxx:44–55

-

Teagle SE (2002) Parental problem recognition and child mental wellness service utilize. Ment Health Serv Res 4:257–266

-

Sayal K, Goodman R, Ford T (2006) Barriers to the identification of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:744–750

-

Yeh M, Forness South, Ho J, McCabe K, Hough RL (2004) Parental etiological explanations and disproportionate racial/ethnic representation in Special Education Services for youths with emotional disturbance. Behavioural Disorders 29:348–358

-

Dempster R, Wildman B, Keating A (2013) The role of stigma in parental aid-seeking for child behavior issues. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 42:56–67

-

Gronholm PC, Ford T, Roberts RE, Thornicroft G, Laurens KR, Evans-Lacko S (2015) Mental health service use past immature people: the function of caregiver characteristics. PLoS I 10:e0120004

-

Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJ, Burns DD (2004) Gaps in accessing treatment for feet and depression: challenges for the delivery of intendance. Clin Psychol Rev 24:583–616

-

Owens PL, Hoagwood Grand, Horwitz SM, Leaf PJ, Poduska JM, Kellam SG et al (2002) Barriers to children's mental wellness services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 41:731–738

-

Briggs-Gowan MJ, Horwitz SM, Schwab-Stone ME, Leventhal JM, Leaf PJ (2000) Mental health in pediatric settings: distribution of disorders and factors related to service employ. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 39:841–849

-

Sayal G, Taylor East (2004) Detection of kid mental health disorders by full general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 54:348–352

-

Stiffman AR, Pescosolido B, Cabassa Fifty (2004) Building a model to understand youth service access: the gateway provider model. Ment Health Services Res 6:189–198

-

Kazdin AE, Holland 50, Crowley M (1997) Family experience of barriers to treatment and premature termination from child therapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 65:453–463

-

Kazdin AE, Wassell Grand (2000) Predictors of barriers to treatment and therapeutic alter in outpatient therapy for antisocial children and their families. Ment Wellness Serv Res 2:27–twoscore

-

Gulliver A, Griffiths KM, Christensen H (2010) Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 10:113

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

-

Kmet L, Lee R, Melt L (2004) Standard Quality Cess Criteria for Evaluating Primar Research Papers from a Varierty of Fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research

-

Dixon-Wood One thousand, Shaw RL, Agarwal South et al (2004) The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care 13:223–225

-

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers G, et al (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme

-

Harwood MD, O'Brien KA, Carter CG, Eyberg SM (2009) Mental wellness services for preschool children in primary care: a survey of maternal attitudes and beliefs. J Pediatr Psychol 34:760–768

-

Larson J, Stewart M, Kushner R, Frosch E, Solomon B (2013) Barriers to mental health care for urban, lower income families referred from pediatric primary care. Adm Policy Ment Health 40:159–167

-

Shun Wilson Cheng W, Fenn D, Le Couteur A (2013) Understanding the mental wellness needs of Chinese children living in the Due north E of England. Ethn Inequal Health Soc Care 6:16–22

-

Eapen V, Ghubash R (2004) Help-seeking for mental health problems of children: preferences and attitudes in the United Arab Emirates. Psychol Rep 94:663–667

-

Sayal Grand, Mills J, White Yard, Merrell C, Tymms P (2015). Predictors of and barriers to service use for children at adventure of ADHD: longitudinal study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24: 545–52

-

dosReis S, Barksdale CL, Sherman A, Maloney Yard, Charach A (2010) Stigmatizing experiences of parents of children with a new diagnosis of ADHD. Psych Serv 61:811–816

-

Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg M, Noguchi K, Bricklayer D, Mayerson G, Garvan CW (2012) Willingness to utilise ADHD treatments: a mixed methods written report of perceptions by adolescents, parents, health professionals and teachers. Soc Sci Med 74:92–100

-

Boulter Eastward, Rickwood D (2013) Parents' experience of seeking aid for children with mental health bug. Advances in Mental Health 11:131–142

-

Sayal M, Tischler V, Coope C, Robotham S, Ashworth Yard, Day C, Tylee A, Simonoff East (2010) Parental help-seeking in principal intendance for child and adolescent mental health concerns: qualitative study. Brit J Psychiat 197:476–481

-

Murry VM, Heflinger CA, Suiter SV, Brody GH (2011) Examining perceptions about mental health intendance and help-seeking among rural African American families of adolescents. J Youth Adolesc 40:1118–1131

-

Bussing R, Zima BT, Gary FA, Garvan CW (2003) Barriers to detection, help-seeking, and service use for children with ADHD symptoms. J Behav Health Serv Res 30:176–189

-

Thurston IB, Phares V (2008) Mental wellness service utilization among African American and Caucasian mothers and fathers. J Consult Clin Psychol 76:1058

-

Meredith LS, Stein BD, Paddock SM, Jaycox LH, Quinn VP, Chandra A et al (2009) Perceived barriers to treatment for boyish low. Med Care 47:677–685

-

Girio-Herrera E, Owens JS, Langberg JM (2013) Perceived barriers to help-seeking amongst parents of at-risk kindergarteners in rural communities. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 42:68–77

-

Mukolo A, Heflinger CA (2011) Rurality and African American perspectives on children'south mental health services. J Emot Behav Disord xix:83–97

-

Sawyer MG, Rey JM, Arney FM, Whitham JN, Clark JJ, Baghurst PA (2004) Use of health and school-based services in Australia by young people with attention-arrears/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Kid Adolesc Psychiatry 43:1355–1363

-

Pavuluri MN, Luk SL, McGe RO (1996) Help-seeking for behavior problems by parents of preschool children: a community written report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:215–222

-

Gonçalves G, Moleiro C (2012) The family-schoolhouse-master care triangle and the admission to mental wellness care among migrant and ethnic minorities. J Immigr Minor Health xiv:682–690

-

Pailler ME, Cronholm PF, Barg FK, Wintersteen MB, Diamond GS, Fein JA (2009) Patients' and caregivers' behavior about low screening and referral in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 25:721–727

-

Chapman MV, Stein GL (2014) How do new immigrant Latino parents interpret trouble behavior in adolescents? Qual Soc Piece of work 13:270–287

-

Pullmann Doctor, VanHooser S, Hoffman C, Heflinger CA (2010) Barriers to and supports of family participation in a rural system of care for children with serious emotional problems. Community Ment Health J 46:211–220

-

Lindsey MA, Chambers G, Pohle C, Beall P, Lucksted A (2013) Agreement the behavioral determinants of mental health service use by urban, under-resourced Black youth: adolescent and caregiver perspectives. J Child Fam Stud 22:107–121

-

Shivram R, Bankart J, Meltzer H, Ford T, Vostanis P, Goodman R (2009) Service utilization past children with conduct disorders: findings from the 2004 Britain kid mental health survey. Eur Kid Adoles Psy 18:555–563

-

Boydell KM, Pong R, Volpe T, Tilleczek M, Wilson Due east, Lemieux Southward (2006) Family perspectives on pathways to mental wellness intendance for children and youth in rural communities. J Rural Health 22:182–188

-

Cohen Eastward, Calderon E, Salinas One thousand, SenGupta S, Reiter Thousand (2012) Parents' Perspectives on Access to Kid and Boyish Mental Health Services. Soc Work Ment Wellness 10:294–310

-

McKay MM, Harrison ME, Gonzales J, Kim 50, Quintana East (2002) Multiple-family groups for urban children with behave difficulties and their families. Psych Serv 53:1

-

Bradby H, Varyani M, Oglethorpe R, Raine W, White I, Helen M (2007) British Asian families and the use of child and adolescent mental health services: a qualitative study of a hard to attain group. Soc Sci Med 65:2413–2424

-

Berger-Jenkins Eastward, McKay M, Newcorn J, Bannon W, Laraque D (2012) Parent medication concerns predict underutilization of mental health services for minority children with ADHD. Clin Pediatr 51:65–76

-

Crawford T, Simonoff Eastward (2003) Parental views about services for children attending schools for the emotionally and behaviourally disturbed (EBD): a qualitative analysis. Child Intendance Health Dev 29:481–491

-

Klasen H, Goodman R (2000) Parents and GPs at cross-purposes over hyperactivity: a qualitative study of possible barriers to treatment. Br J Gen Pract l:199–202

-

Semansky RM, Koyanagi C (2004) Child & adolescent psychiatry: obtaining kid mental health services through medicaid: the experience of parents in 2 states. Psych Serv 55:24–25

-

Guzder J, Yohannes Southward, Zelkowitz P (2013) Helpseeking of immigrant and native born parents: a qualitative study from a montreal child day hospital. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 22:275–281

-

Flink IJ, Beirens T, Butte D, Raat H (2013) The Part of Maternal Perceptions and Ethnic Background in the Mental Health Help-Seeking Pathway of Adolescent Girls. J Immigr Minor Health 15:292–299

-

Hickson GB, Altemeier WA, O'Connor Southward (1983) Concerns of mothers seeking care in individual pediatric offices: opportunities for expanding services. Pediatrics 72:619–624

-

Stein SM, Christie D, Shah R, Dabney J, Wolpert M (2003) Attitudes to and knowledge of CAMHS: differences between Pakistani and white British mothers. Kid Adolesc Ment Health 8:29–33

-

Harrison ME, McKay MM, Bannon WM Jr (2004) Inner-city kid mental health service employ: the real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Ment Health J 40:119–131

-

Brown CM, Girio-Herrera EL, Sherman SN et al (2014) Pediatricians May Accost Barriers Inadequately When Referring Low-Income Preschool-Anile Children to Behavioral Wellness Services. J Health Care Poor Underserved 25:406–424

-

Thompson R, Dancy BL, Wiley TR, Najdowski CJ, Perry SP, Wallis J et al (2013) African American families' expectations and intentions for mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health 40:371–383

-

Gerdes Air-conditioning, Lawton KE, Haack LM, Schneider BW (2014) Latino parental help seeking for childhood ADHD. Adm Policy Ment Wellness 41:503–513

-

Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Hoagwood K, Kleinman Grand, Amakawa L, Altschuler E (2009) Service use by at-run a risk youths afterward school-based suicide screening. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48:1193–1201

-

Ho T, Chung Southward (1996) Help-seeking behaviours among child psychiatric clinic attenders in Hong Kong. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 31:292–298

-

Messent P, Murrell M (2003) Research leading to action: a study of accessibility of a CAMH service to indigenous minority families. Child Adolesc Ment Health 8:118–124

Acknowledgements

CC is funded by an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-2014-04-018). The views expressed are those of the authors and non necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Wellness. TR is funded past a University of Reading regional bursary.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed nether the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original writer(southward) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this commodity

Reardon, T., Harvey, K., Baranowska, M. et al. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health issues in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 26, 623–647 (2017). https://doi.org/x.1007/s00787-016-0930-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

Issue Engagement:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0930-six

Keywords

- Mental health

- Children

- Adolescents

- Handling access

- Barriers

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00787-016-0930-6

Post a Comment for "Barriers Families Face When Helping Their Mentally Ill Family Member"